With COVID-19 directives flying thick and fast from both federal and state institutions, many of us may be getting a little confused about precisely what we can and can’t do, as a matter of law. Every day, someone asks my advice about the fine detail – “Can I drive in a car with my friend/spouse/lover/sister/workmate?”, “Can I walk on the beach with a friend?”, “Can I stroll in the park for fresh air?” – and it’s not always easy to give a definitive answer. The reason is the day to day requirements at law are not set in stone but rather, like the crisis itself, they’re in a state of continual flux.

On 18 March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 outbreak in Australia, the Governor-General declared a “human biosecurity emergency,” pursuant to section 475 of the Biosecurity Act 2015 (Cth). That was the first time emergency powers under the Biosecurity Act have been invoked, and it gave the Federal Minister for Health extensive and quite extraordinary powers, including but not limited to:

- setting requirements to regulate or restrict the movement of persons, goods, or conveyances;

- requiring that places be evacuated; and/or

- making directions to close premises.

Under the Biosecurity Act, the Minister may make any direction or requirement necessary to combat COVID-19 or to implement World Health Organisation recommendations for its control. There are some constraints on the Minister’s power; for example, biosecurity directions requiring individuals to undergo a medical examination, provide body samples for diagnosis, or receive specified treatment or medication, can only be authorised under a “human biosecurity control order” made by the Commonwealth Chief Medical Officer or a “biosecurity officer” in relation to persons suspected of having contracted a listed human disease (including COVID-19), but any person who intentionally engages in conduct contravening any Ministerial requirement or direction under the Biosecurity Act commits a criminal offence, punishable by a maximum penalty of imprisonment for five years and/or a fine of 300 penalty units ($63,000).

To further complicate matters, there are now similar provisions under state law authorising the Chief Health Officer to issue directions with which the Queensland public must comply. On 19 March 2020, Part 7A of the Public Heath Act 2005 (Qld) came into effect, empowering the Chief Health Officer to give directions to assist in containing the spread of COVID-19, including orders restricting the movement of Queenslanders, limiting their contact with others, requiring them to stay, or not, at any specified place, and/or anything else the CHO considers necessary to protect public health. Such orders are deemed to take effect as soon as they are published on the department’s website, and failure to comply can result in fines of up to 100 penalty units (approximately $13,345.00).

Additionally, owners and operators of businesses may be notified to open, close, or limit access to their business premises at any time, in any way, and to any extent recommended by the CHO.

In addition to the powers under Part 7A, where there is a “declared public health emergency” (such as COVID-19), emergency officers can do pretty much anything they reasonably believe is necessary, including requiring people to answer their questions, to not enter or to remain in a particular place, to stop using a place for a stated purpose, to go to a nominated place, to stay at or in a stated place, to destroy and/or dispose of their pets, to clean, to disinfect, and even to shower themselves. Once again, failure to comply with any such order can result in fines of up to 100 penalty units (approximately $13,345.00).

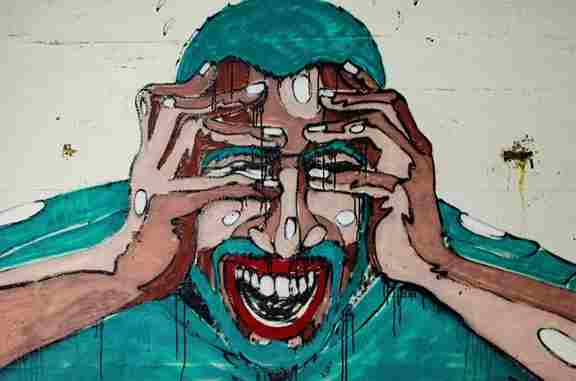

These are extraordinary and potentially draconian powers, but the argument goes that desperate times call for desperate measures.

Few would argue with that sentiment in the context of the current ongoing health emergency, but the challenge for all Australians will be to demand and ensure that, once the crisis has passed, the civil rights we have gladly surrendered in the cause of the common good, will be reinstated as promptly and graciously as they were taken away.